In the last week of February 2020, stock markets worldwide reported their largest one-week decline since the 2008 financial crisis, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average and S&P 500 falling by 12% and 11%, respectively. Since then, with the spread of the coronavirus across the U.S., market shocks have occurred daily. In the month of March alone, the S&P 500 fell by more than 7% in a day on three separate occasions – triggering circuit breakers and temporarily halting trading.

The large day-to-day jumps in the stock market may entice some investors to try to time the market. However, market timing – buying low and selling high – has historically proven elusive for the majority of investors. In the face of increased market volatility, one of the most enduring and commonly touted investment strategies is dollar-cost averaging, the process of investing a specific dollar amount in a stock or mutual fund on a regular basis in order to reduce the impact of market volatility.

In this study, we examined the theory of dollar-cost averaging, and how it plays out in practice, by applying it to four historical examples. Using our own research along with findings from investment company Vanguard and investment management advisory Gerstein Fisher, we discuss when dollar-cost averaging may be most and least beneficial as an investment strategy. We also discuss the importance of considering one’s personal financial goals before employing an investment strategy and why it may be useful to seek out expert advice. For details on our data sources and how we put the information together to create our findings, check out our Data and Methodology section below.

Key Findings

- Many Americans are already dollar cost-averaging. By diverting a pre-tax portion of each paycheck into a retirement account, many individuals, perhaps unknowingly, dollar-cost average through their 401(k)s.

- Dollar-cost averaging can mitigate market volatility. By putting a set amount into the market on a recurring basis, an investor buys more shares when the price is low and fewer shares when the price is high. Therefore, a dollar-cost averaged investment is not tied to the price of a mutual fund or stock at one point in time, but its average price over the course of the investment period. For a lump-sum investment, on the other hand, the price per share is tied to the price of a mutual fund or stock at one point in time.

- Lump-sum investing generally outperforms dollar-cost averaging. In two of the four historical scenarios we analyzed (the Great Recession and the December 2018 market correction), dollar-cost averaging outperforms lump-sum investing, but they represent unique downturns. Markets typically trend upward and provide few opportunities to buy more shares when the price of a stock is low, so lump-sum investing tends to provide larger returns than incremental investing. It also reaps the full benefit of compound interest.

- Investors may still prefer to dollar-cost average their money. While lump-sum investing can often pay off, putting a sum of money in the market all at once can be frightening. Dollar-cost averaging is also a more realistic investment method for many Americans who earn investable money gradually, rather than in lump sums.

The Basics of Dollar-Cost Averaging

Though there are a variety of strategies people use to mitigate risk when investing money, one of the most common strategies is dollar-cost averaging. Also known as the constant dollar plan, dollar-cost averaging is the process of allocating equal dollar amounts to a security according to a set schedule. Rather than investing a lump sum of money upfront, investors put the money to work over a period of time. Because the dollar amount invested is the same at each scheduled interval, the number of shares purchased depends on the price per share.

According to the equation above, the number of shares purchased and price per share are inversely related. The number of shares purchased will be greater if the price per share is lower, while the number of shares purchased will be smaller if the price per share is higher. As a result, dollar-cost averaging necessitates that you buy more shares when the price is low and fewer shares when the price is high.

Understanding How It Works: Historical Examples

The theory of dollar-cost averaging is complicated, so we looked at four different historical scenarios using the same mutual fund and initial investment amount to illustrate how this investment strategy works in practice.

Suppose you have $10,000 to invest. You are generally risk-averse and have decided to add the money to a mutual fund invested 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds – Vanguard STAR Fund (Ticker: VGSTX). Which strategy performs better over a 10-month time period: investing the money in a lump sum or dollar-cost averaging?

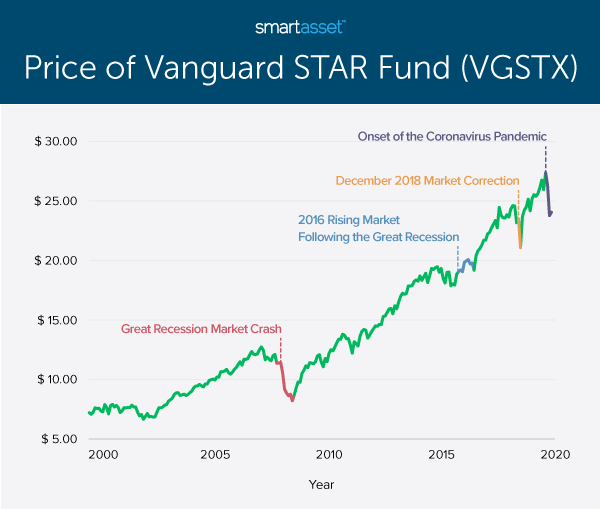

The answer is determined by which time period you consider. The graph below shows the price of Vanguard STAR Fund over the past 20 years. From May 1, 2000 through April 1, 2020, the price grew by more than 200% from $7.21 per share to $24.06 per share.

Scenario 1: Market Crash During the Great Recession

Despite long-term growth, the mutual fund has had distinct periods during which the share price fell. During the Great Recession, the fund fell from an October 2007 peak of $12.74 per share to a February 2009 trough of $8.21 per share.

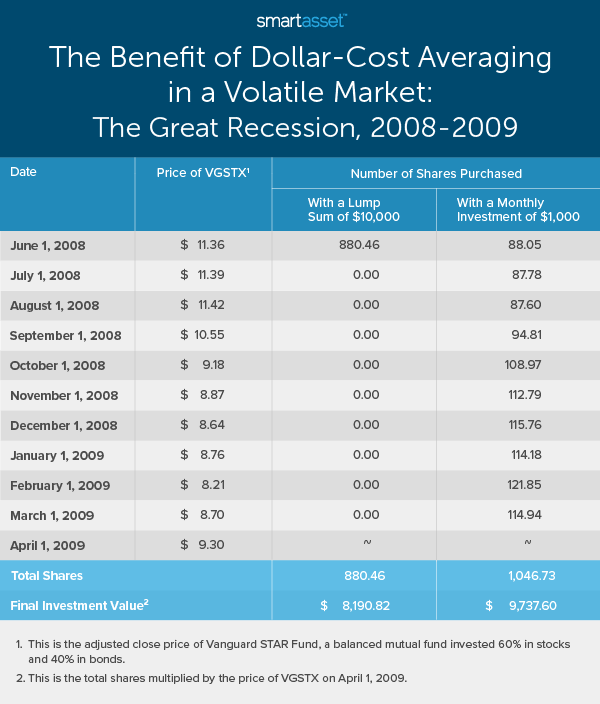

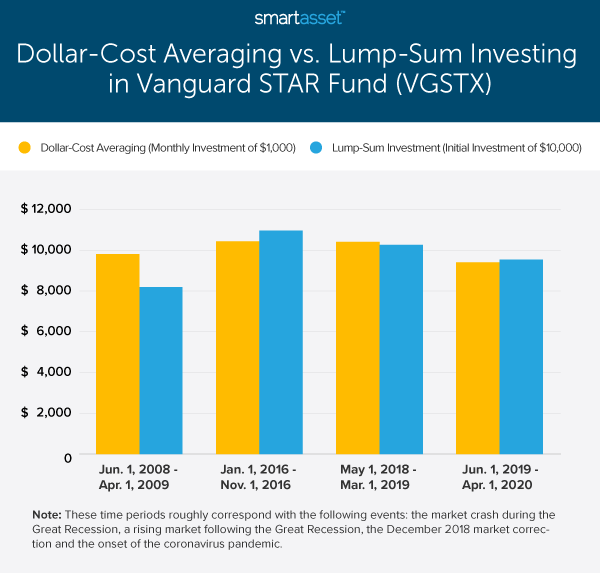

During the Great Recession, dollar-cost averaging investments into Vanguard STAR Fund would have outperformed a lump-sum investment. The table below compares the two strategies over the 10-month period from June 2008 to April 2009.

On June 1, 2008, the price on Vanguard STAR Fund was $11.36 per share. If someone were to invest $10,000 all at that time, he or she would have purchased roughly 880 shares at once. Someone who decided to dollar-cost average, investing $1,000 every month instead, would have purchased 88.05 shares on June 1, 2008, 87.78 shares on July 1, 2008, and so on. Since the share price generally fell from August 2008 to February 2009, monthly investments of $1,000 would have bought more shares. In total, someone who used a dollar-cost averaging strategy over that period of time would have had more than 1,046 shares by the end of 10 months.

Though both strategies in this example result in a loss on the $10,000 investment, an investor using dollar-cost averaging would have lost less. At the April 1, 2009 price of $9.30 per share, the lump-sum investor’s 880.46 shares are equal to about $8,191 while the 1,046.73 shares for the dollar-cost averaging investor are equal to almost $9,738.

Scenario 2: Rising Market Following the Great Recession

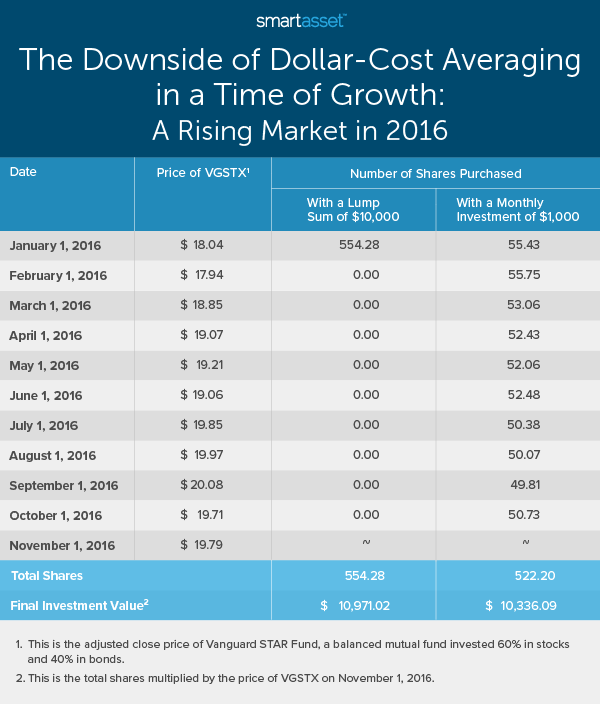

In contrast to the above time period, dollar-cost averaging would have underperformed a lump-sum investment in Vanguard STAR Fund during a period of steady market growth. The table below compares a lump-sum investing strategy and dollar-cost averaging strategy for the period from January 2016 to November 2016.

On January 1, 2016, the price of Vanguard STAR Fund was about $18 per share. Over the course of the subsequent 10 months, the share price grew steadily, despite small downturns. The closing price per share on November 1, 2016 was $19.79, almost 10% higher than on January 1. As a result of that growth, a lump-sum investing strategy would have outperformed a dollar-cost averaging strategy. An investor who bought $10,000 worth of shares at the beginning of the year would have ended with an investment worth almost $11,000. Meanwhile, due to the increase in share price, the dollar-cost averaging investor would have had to buy fewer and fewer shares with each $1,000 monthly investment, making their final investment worth only about $10,300.

Scenarios 3 & 4: December 2018 Market Correction & 2020 Onset of the Coronavirus Pandemic

To examine the December 2018 market correction, we examined the time period from May 1, 2018 to March 1, 2019, and to study the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, we looked at the time period from June 1, 2019 to April 1, 2020. The bar graph below shows the ending amount of a $10,000 investment using both dollar-cost averaging and lump-sum investing strategies during both of those scenarios along with the two previously discussed. Dollar-cost averaging would have performed better than lump-sum investing during the Great Recession and the December 2018 market correction.

When Is Dollar-Cost Averaging Most and Least Beneficial?

Dollar-cost averaging outperforms lump-sum investing in two of the four scenarios we considered, splitting the results down the middle. Where does this leave us?

According to Vanguard research, because markets have historically trended upward, lump-sum investing outperforms dollar-cost averaging more than two-thirds of the time. This research is corroborated by a paper from Gerstein Fisher. Researchers found that although risk-averse investors may favor dollar-cost averaging and be unwilling to invest their assets all at once, lump-sum investing tends to provide larger returns. Dollar-cost averaging generally only outperforms lump-sum investing during times of high market volatility, seen by the Great Recession and the December 2018 market correction.

However, there are two important caveats to when lump-sum investing outperforms dollar-cost averaging. The first is the fact that most Americans are unlikely to receive a large amount of money all at once. With the exception of perhaps a pension payout or an inheritance, it’s more likely than not that individuals will earn investable money gradually. Thus dollar-cost averaging may be a default strategy by design, since investing the money as a lump sum is not possible. For instance, many individuals, perhaps unknowingly, already dollar-cost average through their 401(k)s, diverting pre-tax portions of their paychecks (in a traditional plan) on a monthly basis into a retirement account. If you already have a 401(k), our calculator can help you determine what you saved for retirement so far and how much more you may need.

Second, the investment goals and risk tolerance of individuals matter greatly. The downside of investing a lump sum is that it may be greatly impacted by short-term moves in the market, such as those that have recently occurred due to economic effects of the coronavirus crisis. If an investor is looking to increase their investment over a short time period or has a lower risk tolerance, dollar-cost averaging may still be the better option. For insight regarding your particular situation, consider speaking to a professional financial advisor.

Data and Methodology

Research for this study comes primarily from Vanguard’s 2016 analysis, “Invest now or temporarily hold your cash?” and Gerstein Fisher’s 2011 paper, “Does Dollar Cost Averaging Make Sense For Investors? DCA’s Benefits and Drawbacks Examined.” The prices used for Vanguard STAR Fund are adjusted close prices on the first of each month. Data for this comes from Yahoo Finance. For the purposes of this study, we assumed zero transaction costs.

Tips for Maximizing Your Investments

- Take advantage of compound interest. One of the most important things to note about saving is that it helps to start early. Waiting to invest can potentially decrease your total return on a potential investment. Compound interest is interest that’s generated from existing earnings. In other words, when you put money into a savings account earlier, the interest compounds. As a result, you earn interest on the money you initially invested as well as the interest that money has already made. To see how this works, take a look at our investment calculator.

- Some kind of retirement account is better than none. If a 401(k) is not available through your job, consider an IRA. 401(k)s are often valued more than IRAs since there is a possibility that your employer will match your contributions to the plan up to a certain percentage of your salary. This means that if you choose not to contribute, you are essentially leaving money on the table. However, if your employer does not offer a 401(k) plan, an IRA is another great option. In 2020, the IRA contribution limit is $6,000 for people under 50 and $7,000 for people age 50 and older.

- You don’t have to go at it alone. Investing is complicated. Beyond differences between lump-sum investing and dollar-cost averaging, investors must consider their overall asset allocation in the context of their investment time horizons and financial goals. A financial advisor can help you make smarter financial decisions and be in better control of your money. Finding the right financial advisor that fits your needs doesn’t have to be hard. SmartAsset’s free tool matches you with financial advisors in your area in 5 minutes. If you’re ready to be matched with local advisors that will help you achieve your financial goals, get started now.

Questions about our study? Contact us at press@smartasset.com

Photo credit: ©iStock.com/SARINYAPINNGAM