Craft brewing, or more specifically home brewed craft beer has long been associated with beer nerds. You know, the kinds of people who spend a little too much time coiffing their mustaches, and breaking down the finer points of hops. For the longest time they were the ones at the very bottom of your dinner party invitation list. That is in until craft brewing became cool and exploded into a multi-billion dollar subset of America’s beer infatuation. The above is, of course, false- beer nerds have always been cool. Rather it’s the tastes of American beer consumers that have changed leading to a mass revolt against the tyranny of blandness sold by two titanic beer conglomerates: AB InBev and SAB Miller.

Find out now: What will it cost to go to school?

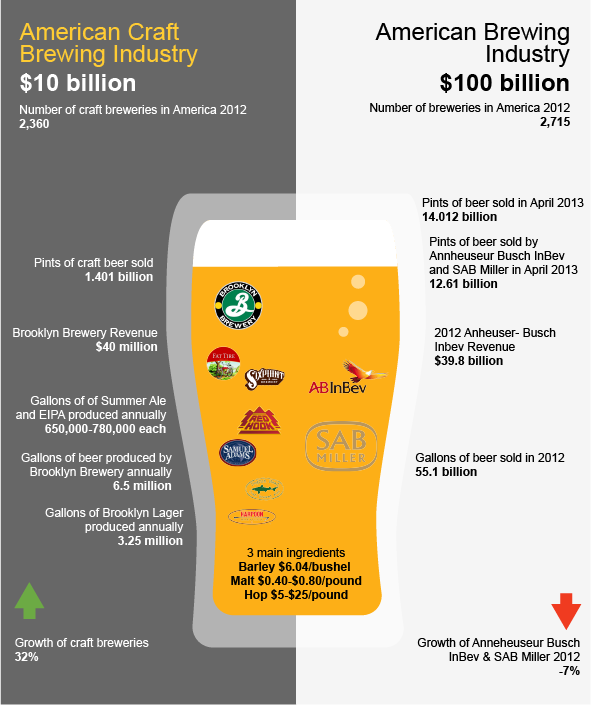

Americans love beer and they consume it in egregious quantities. In 2012 over 55.1 billion gallons of beer were sold across the United States, and 14.1012 billion pints were sold in April 2013 alone. 12.61 billion of which were brewed and bottled by just two companies: Annheusuer Busch InBev and SAB Miller.

However this ability to consume mass quantities of beer doesn’t exactly correlate to an appreciation of beer. In fact AB InBev is currently fighting a lawsuit against accusations of deliberately diluting its products. This is great news for smaller craft breweries. While beer drinkers have grown disillusioned with mass produced beers craft breweries have witnessed as much as 32% growth per year. In the same time while the two heavyweights have seen their market share wither by 7%. This largely attributed to an evolving palates and an increased appreciation of American beer in general.

Craft beer business 101

In 2012, the Brewers Association reported that were 2,715 breweries compared to just 50 in 1980. This isn’t the first time this has happened either. American brewing experienced its first boom back in 1880 and we may be in the middle of a return to normalcy thanks to relaxed regulations, and the internet.

Leading the charge back to the future are two companies: Boston Beer Company (who you may know as Samuel Adams, Twisted Tea and Angry Orchard), and Craft Brewing Alliance (Redhook Brewery, Widmer Brothers Brewing, Kona Brewing Company and Omission Beer). Alongside Sierra Nevada and Belgium Brewing, Boston Beer Company and Craft Brewing Alliance dominate the $10 billion per year craft beer segment.

Related Article: The Best Cities for Beer Drinkers

Boston Beer Company, aka Samuel Adams, has been a part of the craft brewing explosion for close to 30 years. It began in 1984 when its founder Jim Koch literally walked door to door across Boston selling a version of his family’s home brew to local bars owners. In the process he made a lot of friends and built the most profitable company in the craft beer segment. Boston Beer Company was among the first craft brewers to go to public in the 1990’s. It was first initially offered on the New York Stock Exchange at $15 per share. Boston Beer Company (ticker: SAM) currently trades at over $165 per share (6/12/2013).

In 2012 the Boston based brewing company brought in over $580.2 million in revenue and is expected to bring in $664.4 million in 2013. That translates roughly to a per barrel revenue of $213.9 according to Deutsche Bank analysts. After everything is said and done Boston Brewing should take in a total of $59.5 million in profits, all in the name of high quality beer.

Samuel Adams isn’t all about profits thought. It’s thoroughly committed to brewing great beers and making sure other breweries have access to the same great ingredients it does at a fair price. The brewing company, in conjunction with Accion, offers a micro-loans program to small breweries. The loans range from $500-$25,000 and include various forms of support for budding beer entrepreneurs.

The most popular of which is a hops sharing program which launched in 2008. The program was effective in helping struggling breweries acquire several popular types of hops used in India Pale Ales (IPAs). Through the program Sam Adams offered up nearly $200,000 worth of hops split between 10,000 pounds of Simcoe, 10,000 pounds of Citra and 10,000 pounds of Ahtanum hops at $6.50 per pound. Simcoe hops, for example can sell for as much as $15-$20 per pound through some online wholesalers.

Sam Adams’ programs highlight the very real concerns craft brewers have about continued access to quality ingredients. We spoke to Brooklyn Brewery’s General Manager, Eric Ottaway, who also expressed increasing concern about access to ingredients like malt, barley and hops.

“The availability and cost of raw materials are our biggest concerns going forward. Ten years ago we [Brooklyn Brewery] never thought about ingredients- we just came up with a beer recipe and called the supplier for the required malt and hops. Those days are long gone. If you don’t have contracts for your malts and hops, chances are you won’t be able to get them. That makes new beer development pretty tricky- you can’t assume that you will be able to get the ingredients you need. Often you can’t.”

Ottaway continued, “Malt and hops, with the former in particular, are subject to global forces that have nothing to do with craft beer, or even the general beer industry. Barley is a global commodity linked to wheat, corn, and soybeans, and all of those are subject to weather, alternative fuels, and government policy. All four of those crops are very substitutable as animal feed, where the vast majority of it goes, so they tend to rise and fall together. If the corn crop gets wiped out by drought in the US (like last year), the price of barley goes up. If Russia has a heat wave that kills their wheat crop, the price of barley goes up. If the US government mandates more ethanol in our gas supply, the price of barley goes up. The last five years with all the erratic weather we’ve had around the world have been pretty rough!”

That said, the availability and cost of raw materials is a major concern for the craft brewing industry overall. The creation of new beer recipes is increasingly dictated by the terms of established supply contracts. It also doesn’t help that barley, one of the main ingredients in beers like Brooklyn Lager, is a commodity that has seen prices nearly double since 2010. Where a bushel of barley used to cost $3.64 it now trades for $6.07 per bushel.

From garage brewer to beer god

The story behind Brooklyn Brewery’s growth is fascinating, and is a definite source of inspiration for any aspiring entrepreneur or craft beer buff.

Born out New York’s home brewing scene in the 1980’s, the company began as a neighborly project between Associated Press correspondent Steve Hindy and Tom Potter in their Park Slope apartment. Hindy had been introduced to home brewing through Western diplomats stationed in the Middle East. Desperate for a cold beer and unable to find any locally, they resorted to brewing their own. Hindy brought the knowledge back with him when he returned to Brooklyn. The equipment Hindy and other home brewers used can easily be purchased online. Prices range from $40 to $335 for more advanced kits.

Since then, Brooklyn Brewery has experienced tremendous growth , much of which can be attributed to the growth and fascination with independent culture. In 1996 it opened up the doors to its facilities in Williamsburg, Brooklyn at a time when the area was little more than a sketchy industrial zone in the shadows of Manthattan. Then properties in area were valued at $10 to $20 per square foot. However the seeds of gentrification had been planted, as many artists were increasingly calling Williamsburg home in an effort to recreate the feel of “Paris during the 50’s.”

Today Brooklyn Brewery’s facilities, made up of three buildings on three blocks of prime hipster real estate, neighbor VICE Magazine headquarters, Brooklyn Bowl, high end luxury apartments and some of the most popular nightlife destinations in New York City. The buildings which include 21,000 square foot brewing space, 4,000 square foot event space and ab 35,000 square foot warehouse have a current market value of $896 per square foot. An increase of over 4000% since 1996. A residence the size of the facilities would cost an estimated $53.46 million in today’s market.

More valuable than its land (at least to us) is the beer Brooklyn Brewery produces. In 2012 it bottled, barreled and canned over 5.4 million gallons of beer helping to generate $40 million in revenue. Ottaway estimates the brewery will bring 6.5 million gallons to market by the end of 2013.

So how do you become the next Brooklyn Brewery, Samuel Adams, Red Hook Brewing or the thousands of other breweries concocting some delicious bread water? Simple, just buy yourself a brewing kit, find a recipe you like and start brewing.

The economics of small to midsize craft brewing

Today the main ingredients in beer- malt and hops- can be purchased online or through easy to reach wholesalers. Brooklyn Lager, which makes up 50% of Brooklyn Brewery’s production, uses American two-row malts and Hallertauer, Mittelfrueh, Vanguard and Cascade hops. The hops can vary greatly in price from as little as $5 per pound to as much as $25 per pound. The price of malt is more consistent, ranging from $.40 per pound to $.80 per pound. Brooklyn Brewery will use 6 million pounds of malt and spend between $2.4 million to $4.8 million in the creation of Brooklyn Lager alone.

While these may seem like massive numbers that help to drive down the costs of acquiring ingredients, Ottaway was quick to remind us that this pales in comparison to larger companies like ABInBev or SAB Miller. In other words, the amount Brooklyn Brewery spends in the production of Brooklyn Lager is very similar to what any upstart craft brewing company would pay on day one of business. That’s not to say that Brooklyn Brewery does not benefit from its size.

“The improvement in efficiency comes mainly from running larger brewhouses. If you have a 100 BBL brewhouse, compared to a 10 BBL brewhouse, one brewer can make ten times more beer. Your cost per lb of raw materials is pretty close, but your labor is obviously much more efficient.” Ottaway said.

Ottaway added that “the biggest costs in bottling are the bottles themselves. A case of 24/12oz bottles costs around $3.50, and then your packaging, labor, and depreciation of the bottling line make up the rest, after the beer of course. There is a wide range of total costs in making a case of beer, driven by the style of the beer and the size of the run. High ABV, high hop beers are much more expensive to brew, and smaller runs have much higher packaging costs due to small packaging material runs.”

The greatest opportunity for companies like Brooklyn Brewery and Six Point, is in reducing packaging costs. This is witnessed in the market shift from bottles to cans.

“There are an increasing number of breweries coming out with cans,” Ottaway told SmartAsset, “and several are even can only, no bottles. Two things have enabled this- the development of smaller sized canning lines which make it more affordable for craft brewers to get into canning, and the ability of the can producers to do smaller can runs for craft brewers. The last piece of course is the increasing acceptance by consumers of the can as an acceptable package for craft and specialty beers. Cans are lighter, cool down more quickly, and are better for the beer since they block out 100% of the light. What’s not to like?”

Craft brewers are also increasingly victims of their own success, as they fight to gain the attention and respect of distributors and government alike. Currently small brewers are taxed $7 for 31 gallons they produce. That works out to roughly a 22% tax on every barrel of beer that leaves their breweries. That is, if it leaves the brewery. Ottaway notes that for the first 20 years of Brooklyn Brewery’s existence larger distributors were clueless as to how they could get their product in to stores and bars.

“By 2003 we had grown enough that we were able to sell the distribution rights to a big distributor. At our size today, distribution is no longer an issue as every distributor in the country wants the top craft brewers in their portfolio. It took a long time to get to that point though. Today the problem is the opposite- there are too many craft breweries for the distribution channel to handle effectively. In other words, the distribution channel is clogged. A new brewery today is more likely to have to think about self-distribution again until they have enough size that a regular distributor can handle them. It’s not a question of interest anymore- the big distributors are very interested- it’s a question of whether they have room in their portfolio.”

What is interesting about the growth of the craft brewing industry is its connection to changing consumer culture. As Americans have become smarter and worldlier, they’ve also become increasingly urban and environmentally conscious. This heightened sense of consciousness about what is consumed, how it’s made, and a willingness to pay top dollar for it is driving the demancd for craft beer. However, that consciousness is also likely to be one of the biggest threats to the industry’s continued growth.

Short sighted policies that attempt to “green” the image of government and large corporations through the increased use of bio-fuels are driving up costs for many brewers. Making it increasingly difficult for some of the nation’s most vibrant small businesses to survive. Being green for the sake of green ultimately hurts the consumer in the long run.

Tips for Starting a Small Business

- If all this talk about the economics of beer is making you consider turning your home brewing hobby into a business, make sure you have a plan in place before you make the hop. Many financial advisors specialize in serving business owners, and they can help you plan and invest strategically. The SmartAdvisor matching tool can help you find a person to work with to meet your needs. First you’ll answer a series of questions about your situation and your goals. Then the program will narrow down your options to three fiduciaries who suit your needs. You can then read their profiles to learn more about them, interview them on the phone or in person and choose who to work with in the future. This allows you to find a good fit while the program does much of the hard work for you.

- You’ll need to cover more than the cost of brewing equipment if you get into the beer business. You’ll also have to pay small business taxes, which tend to be more complicated than individual income taxes. SmartAsset’s guide to small business taxes can give you an overview.

Photo Credit: flickr, Brooklyn Brewery, OregonLive.com

Source: Brooklyn Brewery, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, New York Times, NPR, BBC UK, Brewers Association