New Jersey imposes a mansion tax on real estate transactions that exceed $1 million. This 1% levy applies to residential and certain commercial properties, adding a significant cost for high-value buyers. The tax is typically paid by the purchaser at closing, though exemptions and legal strategies may help reduce or eliminate the obligation. Buyers looking to avoid or minimize the New Jersey mansion tax often explore exemptions for specific property types, ways to structure purchases that escape the tax or negotiations with sellers.

A financial advisor can help you make major financial decisions, like purchasing a home or retiring. Connect with your advisor matches.

Understanding the NJ Mansion Tax

New Jersey introduced the mansion tax in 2004 as a way to generate revenue from high-value real estate transactions. The tax applies to residential and many commercial properties sold for more than $1 million. The tax is normally paid by buyers at closing at the rate of 1% of the purchase price. Unlike the state’s realty transfer fee, which applies to a broader range of transactions, the mansion tax specifically targets luxury sales.

The tax applies to single-family homes as well as small multi-family properties, including condos and co-ops, with fewer than four units. Commercial properties such as office buildings are also covered. Buyers must pay the tax directly to the county recording office at closing, and failure to do so can delay the recording of the deed.

Who Pays the NJ Mansion Tax?

While the legal obligation falls on the buyer, some sellers may agree to cover part or all of the tax as a negotiation tactic. This is especially likely in a buyer’s market. However, buyers should typically budget for this added tax as part of closing costs.

Sales involving government entities or qualified affordable housing programs may be exempt. Other property types not covered by the mansion tax include vacant land, farms with no residences, industrial properties, churches, schools and properties owned by charities.

Some types of transactions are also not covered by this tax. They include transfers between relatives, those resulting from bankruptcy, divorce or as stipulated in a will.

NJ Mansion Tax vs. Realty Transfer Fee

The NJ mansion tax and the realty transfer tax serve different roles in real estate transactions. The mansion tax is a targeted surcharge on properties exceeding $1 million, designed to generate revenue from high-end sales. Its threshold does not adjust for inflation or market trends, meaning more properties have become subject to the tax over time as home values have risen since its passage in 2004.

The realty transfer tax, on the other hand, applies to nearly all sales and follows a progressive rate structure, increasing as the transaction amount rises. Unlike the mansion tax, which is a fixed percentage, the transfer tax includes exemptions and reduced rates for certain sellers, such as seniors and first-time homebuyers. While the buyer typically pays the 1% mansion tax, the seller generally covers the realty transfer fee.

Another key difference is how these taxes apply to commercial properties. While the mansion tax applies to mixed-use and commercial properties that include residential components, the realty transfer tax generally applies to all real estate transfers. Exemptions to the realty transfer tax are generally limited to those resulting from bankruptcy, divorce, settling an estate and a few others.

How to Avoid the NJ Mansion Tax

Avoiding the mansion tax in New Jersey requires careful transaction structuring, but options are limited. The most straightforward way is to keep the purchase price at or below $1 million. If a property is priced slightly above this threshold, buyers and sellers may negotiate concessions, such as including furniture or other non-real estate assets in a separate bill of sale to bring the recorded price below the limit. However, artificially reducing the recorded price to evade the tax can violate state laws.

For sales of mixed-use properties, structuring the transaction to emphasize non-residential value may provide an exemption. If the residential portion is a small percentage of the total property, buyers may qualify for relief. Certain government-related transactions, such as those involving affordable housing projects or nonprofit entities, may also be exempt.

Mansion Tax in NJ vs. Other States

New Jersey’s mansion tax stands out for its strict $1 million threshold, which does not adjust for inflation or regional price differences. This contrasts with states like New York, where the mansion tax starts at 1% for properties over $1 million but increases progressively for higher-value transactions.

In states like Connecticut and Hawaii, luxury real estate is also taxed at higher rates, but their structures differ. Connecticut applies a graduated conveyance tax, reaching up to 2.25% on sales exceeding $2.5 million. Hawaii, meanwhile, charges a transfer tax of up to 1.25% on homes worth $10 million or more.

Other states, such as California and Florida, do not have a statewide mansion tax, though high-value real estate sales may be subject to local transfer taxes. Compared to these states, New Jersey’s tax is broad and applies uniformly to all qualifying transactions.

Bottom Line

New Jersey’s 1% mansion tax on properties valued at more than $1 million adds to the cost of high-value property transactions, affecting buyers of residential and certain commercial real estate. While the tax applies broadly, some exemptions and structuring methods may provide relief in specific cases. Buyers and sellers involved in high-end real estate transactions should account for this tax when planning a purchase or sale, as avoiding it entirely is difficult without qualifying for specific exemptions or structuring alternatives.

Tax Planning Tips

- Maximizing your use of tax-advantaged accounts can be a simple but effective tax strategy. Contributing to 401(k) plans, IRAs and health savings accounts (HSAs) can lower taxable income while allowing investments to grow tax-deferred or tax-free. Roth IRA conversions may also be beneficial if tax rates are expected to rise in the future.

- A financial advisor with tax expertise can be a valuable resource as you look for ways to save on taxes. Finding a financial advisor doesn’t have to be hard. SmartAsset’s free tool matches you with vetted financial advisors who serve your area, and you can have a free introductory call with your advisor matches to decide which one you feel is right for you. If you’re ready to find an advisor who can help you achieve your financial goals, get started now.

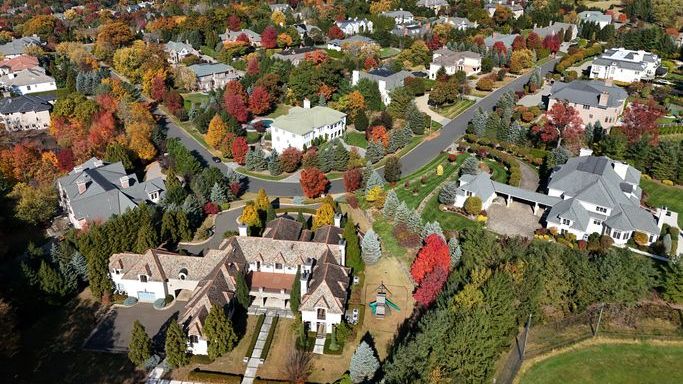

Photo credit: ©iStock.com/Johnrob, ©iStock.com/Johnrob, ©iStock.com/dolah