Check out our Financial Advisor Value Calculator here.

Abstract

Given the diverse spectrum of financial needs and advice, the exact financial impact of employing a financial advisor remains largely unquantified. But with clients putting their hard-earned dollars up for the unknown, it may be difficult to pull the trigger employing a financial advisor, despite the potential for long-term payoffs.

This model aims to quantify the value of a financial advisor by using assumptions that most accurately reflect reality for the majority of individuals. While a financial advisor’s scope for value-add is potentially limitless, the impact of most advice can be traced to the client’s bottom line in one of two ways: Through additional investment gains or tax savings. At the same time, a continuous relationship between client and advisor is necessary to maximize the dollar benefit in each of these areas due to the ongoing and volatile influence of both behavioral and technical factors.

We derive a general value of professional management of these factors using historical data and the circumstances of the client – including age, starting net worth, income and retirement age. And while this model allows for value estimation of the client-advisor relationship at the individual level, it also distills general value ranges:

- After accounting for annual inflation (2.56% annual) and fees (1% or 0.75% of AUM), annual rates of return for those with advisors are estimated to range from 4.56% to 7.57%, representing a 2.39% to 2.78% annual premium over those without an advisor.

- Depending on starting age, clients who employ a financial advisor can see an estimated 36% to 212% more dollar value to their bottom line over a lifetime. Starting net worth also impacts the ultimate value derived: For example, a 45-year-old may see a range of lifetime advisor premium to their net worth at 92% to 113%, depending on how much they start with.

- Advisor fees, generally ranging from 1% to 0.75% annually depending on net worth of the client, make up an estimated 23.0% to 35.4% of the total value surplus generated by the client-advisor relationship.

A financial advisor strategizes both offensively to grow wealth and defensively to protect it, navigating through external factors such as market dynamics, regulatory policies and technological innovation, as well as internal factors such as psychological, emotional and circumstantial nuances that could derail financial success for a client. Such obstacles, often unrecognizable by the layperson, can cost individuals hundreds of thousands of dollars over their lifetime – or more.

While clients are each unique and the breadth of an advisor’s scope is wide, most of the main areas of value-add can be bucketed into an investment (inflows) or tax (outflows) bucket.

To maximize a client’s financial potential, an advisor fields complications posed by the interacting dynamics of behavioral and technical finance components with the goal of maximizing inflows and minimizing outflows.

Behavioral Finance

The first stages of the client-advisor relationship involve the advisor getting to know what makes a client tick. This is not limited to an individual’s financial details: Emotions, attitudes, beliefs, values, goals, biases, family dynamics and more all play a role in personal finance. These influence the chain of events that went into the client’s current financial position and will influence future financial decisions. It is the advisor’s job to dig into these cause-and-effect relationships to best help the client understand and optimize his financial situation moving forward.

Some emotional and experiential dynamics that can affect a client’s decision-making, unbeknownst to them, include:

- Risk capacity, risk tolerance and risk literacy. A client must understand tradeoffs and probabilities for the financial decisions they make. Resources available for reaching various goals may have limitations, so opportunity costs must be understood.

- Family dynamics. The interplay between family members can subtly influence financial decisions. For instance, the desire to maintain harmony or the pressure to conform to family expectations can lead to conservative or, conversely, overly risky investments. A client might inherit financial responsibilities or expectations from their family, like funding a sibling’s business or maintaining a family estate, which might not align with their personal financial strategy or capacity.

- Biases. Cognitive and emotional biases often operate below the conscious level, skewing judgment. For example, confirmation bias might lead a client to favor information that supports pre-existing beliefs about an investment, while loss aversion could prevent them from selling underperforming assets to avoid realizing a loss, missing out on the opportunity for potential gains elsewhere.

- Attitudes, values, and beliefs. A client’s financial choices are deeply rooted in their personal and cultural values. Someone might avoid investing in certain industries due to ethical convictions, or they might prioritize short-term gains over long-term growth due to a belief in living for the moment.

Employing professional knowledge can help clients see their situation independent of these influences. Despite best intentions, a client may have difficulty making optimal decisions due to their personal ties to a situation. But arms-length guidance can prevent costly mistakes that – like good financial decisions and habits – compound over time.

While emotional and psychological biases can be tough to identify from within, they can show up in financial decisions in nearly infinite ways. To demonstrate:

- Sam is a graphic designer who decided to dip his toes into investing with his savings. He chose what he thought were stable, blue-chip companies. All was well until one day in March 2020, when the market plummeted due to a global health crisis. Within weeks, Sam saw his investments drop by half. The visceral experience of watching his hard-earned money vanish in real time made him pull out of the market entirely, wary of its volatility. He now keeps most of his money in CDs.

- Jasmine inherited a set of stocks from her grandfather, who always spoke fondly of the companies. Despite the poor performance of these stocks as of late, Jasmine holds onto them because she attributes sentimental value to these investments. Over time, these stocks continue to underperform, reducing her portfolio’s value significantly compared to what a diversified investment could have yielded.

- Henry, a retired engineer at 65, grew up during a time when owning real estate was seen as the ultimate investment, and he has a significant portion of his wealth tied up in rental properties. As he aged, the management of these properties became more burdensome, and the market dynamics shifted, reducing rental yields. Still, Henry’s attachment to real estate keeps him heavily invested in property. This decision leaves him with liquidity issues and a higher risk exposure than what might be suitable for his age, especially when unexpected repairs or vacancies arise, impacting his fixed income in retirement.

While it may be hard for an individual to spot when he or she is being influenced by biases in the moment, these inclinations can rear their heads in their bottom line regardless of their goals and strategies. One study even puts the cost of emotional investing at up to 5.5% or more annually¹.

Technical Finance

Every person’s financial ecosystem is distinct, with the elements closely interlinked – meaning decisions in one area can trigger a cascade of effects elsewhere. Given this complexity, alongside the ever-evolving landscape of technical finance, generic financial education can only go so far in revealing the full scope of implications for financial decisions.

The main factors at play in this regard include:

- Legislation. Changes in tax laws, investment regulations, or financial reporting standards can significantly alter the landscape of financial planning. For instance, new tax legislation might make certain investments less advantageous, prompting a shift in asset allocation in order to optimize a financial plan within the new legal framework.

- Market dynamics. Investment markets and beyond may be impacted by political changes, shifting economic incentives, trade agreements, asset correlations and more. For example, a new trade agreement could suddenly make an overseas market more accessible or profitable, or a political shift might increase the risk associated with certain assets.

- Technology. Advancements in technology can revolutionize industries overnight, impacting economies and portfolios alike. For example, advancements in artificial intelligence, particularly large language models (LLMs), have revolutionized approaches to customer service, data analysis, marketing and more, potentially cutting operational costs while boosting efficiency and innovation in various sectors.

- Financial products. The introduction of new financial instruments or the evolution of existing ones, like derivatives, ETFs, or life insurance products, can offer new ways for clients to manage risk or seek returns.

Just as behavioral finance influences individual financial conduct, the technical components of finance shape the environment in which these decisions are made. These elements are the structural backbone of personal finance, dictating the rules of the game and the tools available for play. Understanding these components requires a different kind of expertise, one that interprets how laws can shift investment landscapes, how technology might revolutionize transaction methods, how new financial products can alter risk profiles, and how market dynamics reflect and affect global economic sentiments.

These examples demonstrate how the technical aspects of finance can manifest in various critical ways:

- Lila, who works in the renewable energy sector, invested in solar panel manufacturing companies, anticipating growth due to increasing global demand for clean energy. However, she didn’t anticipate the impact of trade wars and tariffs on imported materials essential for solar panel production. The increased costs due to tariffs led to a temporary downturn in the sector, affecting her investments.

- Carlos, a real estate investor, was looking to capitalize on short-term rentals through platforms like Airbnb. However, his city introduced strict regulations on short-term rentals to combat housing shortages, requiring permits and imposing heavy fines for non-compliance. This legislative change significantly altered Carlos’s investment strategy, pushing him towards long-term rentals or seeking properties in less regulated areas, impacting his expected returns and business model.

- Ethan, a recent college graduate, was introduced to robo-advisors for managing his small investment portfolio. Attracted by the low fees and the promise of algorithmic efficiency, he invested his savings without much human oversight. While this worked well for basic investment, Ethan didn’t fully grasp the limitations of algorithms during unusual market conditions, like a flash crash or a sudden sector-specific downturn, which could potentially lead to less optimal investment decisions.

Changes to the technical finance landscape have the potential to drastically alter the course of existing financial plans, and often suddenly. Sometimes, adjustments need to be made with haste.

Financial Planning: The Intersection of Behavioral and Technical Finance

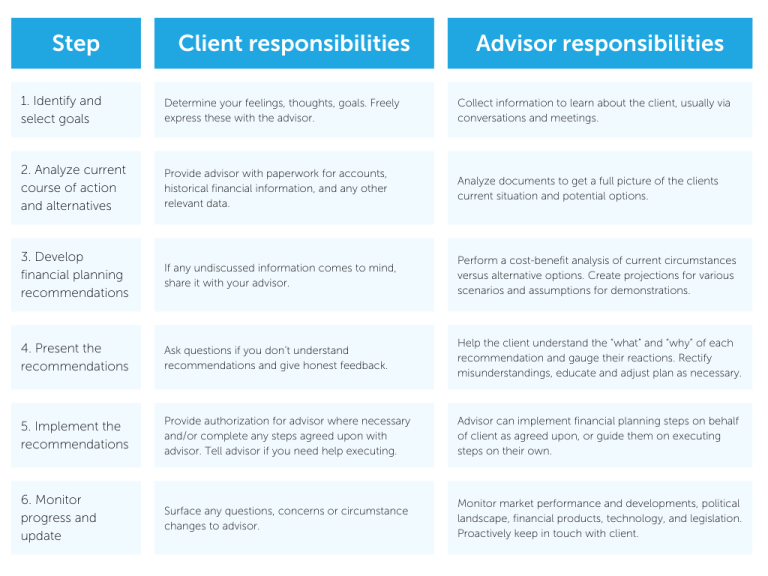

The financial planning process is generally described in seven main steps continuously repeated as new behavioral and technical circumstances arise. These steps are listed below, with details about what the advisor and client should each be doing at each step of the process.

The dynamics of this relationship can also be conceptualized with two vectors representing the continuous forces driving reformation and adjustments in the financial plan over time – forces of behavioral and technical finances, as discussed above:

- Behavioral finance examines how psychological influences and biases affect the financial behaviors of investors and financial practitioners. It focuses on how real people make decisions under uncertainty, integrating elements like risk perception, family dynamics, cognitive biases, and personal values, which often lead to deviations from the rational decision-making models assumed by traditional finance.

- Technical finance deals with the quantitative and structural aspects of finance, including legislative impacts, market dynamics, technological advancements, and the development of financial products. It analyzes how changes in laws, market conditions, technology, and financial instruments directly influence investment strategies, risk management, and financial planning, emphasizing objective analysis and the mechanics of financial systems.

Below is an illustration of the financial advisor’s continuing value based on the dynamic nature of personal finance and its governing principles:

Ultimately, the objective analysis provided by a financial advisor can help integrate complex factors to yield the most optimal results for the client. There is generally not a one-size-fits-all financial solution for financial planning due to all of the moving parts; thus, the advisor’s job is to provide structure among the chaos, guiding clients through the labyrinth of potential financial opportunities and pitfalls.

Projecting the Value of a Financial Advisor

Quantifying the value of a financial advisor is complex due to the diverse and personalized nature of financial advice. Given the impracticality of gathering comprehensive data from all advised and non-advised individuals, we use available data to make reasonable projections, mirroring how advisors themselves forecast financial scenarios for their clients. This model employs proxies and assumptions that reflect the key areas where advisors typically add significant value for most clients.

The myriad ways in which financial advisors add value can largely be distilled into two primary categories: optimizing investments (offensive strategy) and minimizing tax liabilities (defensive strategy). Both behavioral finance and technical finance limitations impact these main value drivers. While the connection between smaller and more varied financial choices and these themes may not always be readily apparent, they ultimately all make their way to a client’s bottom line.

Below is an illustration of how a wide array of financial decisions and techniques can fall into the value buckets of investment gains and tax savings.

A main assumption of this model is that most of the financial outcomes can be reflected in one of these two categories. The following sections demonstrate some of the ways in which these categories may make their way to a client’s bottom line, and how those values will be estimated.

Investment Gains

Investment gains can come in a variety of forms. For example, it’s oftentimes prudent for an advisor to reallocate a client’s portfolio to more closely align with their risk tolerance, time horizons and growth goals. Or, an advisor may be tasked with picking specific investments that align best with the client’s intent and capacities using fundamental and technical analysis, as well as their knowledge of market dynamics. Yet another opportunity may be reallocating investments to areas with lower fees, or accounts with better investment products given the client’s circumstances and goals. But opportunities to grow a client’s net worth can also arise in more obscure ways.

Consider the following scenarios:

- Alex, a 35-year-old self-employed individual, has found recent success with his income doubling in a matter of months. He wants to save more for retirement. His advisor recommends shifting from a Roth IRA, which was limited to $7,000 in contributions annually, to a Solo 401(k). This plan lets Alex contribute up to $23,000 as an employee plus up to 25% of his net business income as an employer in 2024, maximizing his tax-advantaged savings – up to $69,000 in total contributions annually – and better leveraging compound growth for retirement.

- Karen, 54, wishes to retire early but most of her savings are locked in her 401(k). Her financial advisor introduces her to the Rule of 55, explaining that since she’s leaving her job in the year she turns 55, she can start taking penalty-free withdrawals from her current employer’s 401(k) plan. Additionally, the advisor sets up a series of Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (SEPPs) for her IRA under Rule 72(t), allowing her to access funds from there without the 10% early withdrawal penalty. This strategy provides Karen with immediate income while preserving her investments by avoiding penalties, setting her on a path to enjoy an early retirement.

While these examples demonstrate that not all gains are due strictly to choosing specific investments, the total investment impact on a client’s bottom line can be represented by a theoretical advisor alpha – or premium on financial inflows due to the employment of professional guidance. In this model, the benchmark will be an individual who does not employ a financial advisor, and thus does not benefit from expert guidance in their offensive strategy.

So advisor alpha will represent the estimated annual benefit to a client’s net worth due to the bundle of professional guidance in the investment category. Because there is limited investment performance data available for individuals with and without advisors, advisor alpha will be built off the performance of official investment recommendations of professional financial analysts. The performance of these recommendations is compared to the benchmark of S&P 500 returns over the same time period as the recommendations.

A random sample of 45 analysts covering at least one of the 15 largest U.S. companies by market cap was collected from TipRanks.The data included a performance spread of -21.0% to 31.60% compared to the S&P 500, highlighting the risk that is still involved in any investment. Still, the average performance of these analysts relative to the S&P 500 was a positive 2.47%, which will represent the advisor alpha on investment performance in this model².

Although not every individual’s investment strategy will mirror this scenario, the advisor alpha (2.47%) serves as a stand-in for a range of value-added services, including choosing the right accounts, trimming excessive fees, optimizing contribution tactics and much more.

Tax Savings

Tax savings strategies are also often nuanced, extending beyond the obvious credits and deductions and into realms where strategic planning can yield significant benefits. For instance, an advisor might guide a client toward an investing strategy that minimizes tax liabilities, thereby increasing the effective rate of return. Or, they might employ strategies like tax-loss harvesting, where losses are used to offset gains, thereby reducing a client’s tax liability. Another strategy may involve the timing of income and deductions, where an advisor might suggest accelerating or deferring income or expenses to manage the tax bracket effectively year by year.

Consider the following illustrative scenarios:

- Emily, a high-net-worth individual, wants to support her favorite charities but also wishes to minimize her tax burden. Her advisor suggests setting up a Donor-Advised Fund (DAF). By contributing a significant amount in one year, Emily can take a large charitable deduction immediately, potentially dropping her into a lower tax bracket. She can then distribute these funds to charities over several years, smoothing out her donations while maximizing her current tax benefits.

- Tom, who is in good health and has a high-deductible health plan, is advised by his financial planner to maximize contributions to an HSA. Not only does Tom get a tax deduction for his contributions, but the funds grow tax-deferred and can be withdrawn tax-free for qualified medical expenses. However, his advisor points out that after age 65, Tom can use HSA funds for any purpose without penalty, though non-medical withdrawals are taxed as income. This strategy turns the HSA into an additional retirement savings vehicle with unique tax advantages.

To proxy the various ways a financial advisor can help contribute to a client’s tax savings, this model includes the value of savings via professional recommendation, extending to all defensive recommendations that are likely to reach a client’s bottom line. These values will be based on research detailed by Vault Wealth Management, which describes survey results from 2,000 taxpayers.

This survey revealed that taxpayers who employed professional help for their taxes received $840 more than their self-filing counterparts³. Applying the tax savings to the median net worth of $80,039 in the same year⁴, we apply a 1.0495% annual tax savings rate for this model. This will be applied to the client’s concurrent net worth for each year he or she employs a financial advisor as a proxy for defensive-strategy savings.

Several changeable assumptions have an impact on the estimated tax savings an advisor can bring to a client. Namely, the portfolio growth rate, inflation rate, current age and estimated age of death, retirement age, advisor fees and potentially more can affect the actual realized tax savings.

Depreciative Factors

Several other factors affect the long-term value of a financial advisor, namely:

- Inflation eats at the value of the dollar, curtailing the real growth and making future dollars less valuable.

The dollar values in this model will all be inflation-adjusted, using appropriate variations of the inflation-adjusted growth formula:

The average annual inflation rate from 2000 through 2023 was 2.56%⁵, which will be the inflation rate applied in this model.

- Withdrawals, particularly regular portfolio withdrawals in retirement, may reduce the impact of compound growth of an investment portfolio. A common rule of thumb for making a retirement portfolio last is to withdraw 4% of your portfolio annually, and so that will be the assumption in this model.

- Fees for a financial advisor’s services are generally stated annually as a percentage of the client’s net worth, and removed quarterly as the portfolio value changes.

Described in more detail below, fees in this model are assumed to be 1% annually, or 0.25% quarterly, for individuals with a net worth up to $1 million. For those with net worth beyond $1 million, fees drop down to 0.75% annually, or 0.1875% quarterly.

The Model

Investment gains and tax savings will hold the weight of the value of a financial advisor at various incomes, asset levels and ages, while other assumptions such as inflation, portfolio growth, tax savings and length of lifetime will be assumed from historical data. Other inputs such as retirement age and advisor fees are assumed based on industry standards.

These inputs, among others, may all impact the dollar value of a financial advisor for a given client. Just as each person’s circumstances are different, so is the value a person stands to gain from employing professional help.

The model maintains different measurements for the length of a person’s pre-retirement time – or wealth accumulation phase, often the duration of an individual’s career – and retirement time, both with and without the guidance of a financial advisor.

The wealth accumulation phase often includes a portfolio of securities, as well as periodic contributions to investments from the individual’s annual income. The retirement phase generally entails a shift to a more conservative portfolio, often bonds, and includes regular withdrawals from the accumulated net worth. In the case where an individual employs a financial advisor, there is also an assumed annual tax savings above the baseline measurement of someone self-directing their finances, and a fee is taken out of the individual’s net worth on a quarterly basis.

Accounting for these dynamics, the lifetime value of a financial advisor on a client’s net worth can then be measured as the difference between the final net worth at end of life with an advisor and without an advisor. This model is described in the following visual:

Each quadrant can be mathematically estimated with the following equations:

The variables represented above include:

Annual Return Estimates

By applying variations of the inflation-adjusted rate of returns formula discussed in the Depreciative Factors section, we can also derive estimated rates of return for each quadrant to make simple estimates that do not account for other variables such as additional savings contributions and retirement withdrawals.

Using these formulas, the model estimates the annual rate of return for each scenario as follows, using two different rates for advisor fees. These rates can serve for simple estimations of potential portfolio growth without considering the impact of other variables such as age, additional investment contributions and retirement withdrawals. They account for portfolio growth, inflation, advisor alpha, tax savings, and advisor fees where applicable.

Simple rates of return with 1% annual advisor fees:

- Accumulation phase, with an advisor: 7.32%

- Retirement phase, with an advisor: 4.56%

- Accumulation phase, without an advisor: 4.93%

- Retirement phase, without an advisor: 2.15%

Simple rates of return without 1% annual advisor fees:

- Accumulation phase, with an advisor: 7.58%

- Retirement phase, with an advisor: 4.81%

- Accumulation phase, without an advisor: 4.93%

- Retirement phase, without an advisor: 2.15%

Comparing the rates of return with and without an advisor, a simple annual estimate of the value of an advisor would be:

- Accumulation phase, with an advisor: 2.39%

- Retirement phase, with an advisor: 2.78%

- Accumulation phase, without an advisor: 2.64%

- Retirement phase, without an advisor: 2.67%

Fees

Fees paid to a financial advisor cover a wide array of services, acting as an investment in both immediate, tailored advice and as insurance for having expert counsel on call. Ultimately, fees are negotiable between the client and advisor based on the guidance and net worth involved.

This model assumes a common fee structure, where 1% of assets under management are due, proxied generally as 0.25% of the portfolio value each fiscal quarter. Because advisors tend to offer discounts for those with more assets, the fees for beyond $1 million in net worth drops down to 0.75% annually, or 0.1875% quarterly.

This fee structure ensures that clients benefit from proactive planning as well as swift, expert intervention during critical, often unexpected, financial moments, addressing complexities from both psychological and strategic financial perspectives. This retainer model provides peace of mind and immediate access to expertise when market shifts, personal life changes, or unique investment opportunities arise, offering value that’s both strategic and timely.

While fees are already accounted for in the investment savings equation in order to account for simultaneous portfolio growth, we can separate out and represent the total fees paid over a lifetime with the following equation:

While total accumulated fees may seem relatively large according to the initial portfolio value, it’s important to remember these values are lifetime amounts dependent on many factors. And when compared to the client’s bounty from the advisor’s guidance in the investment and tax categories, fees are just a fraction of the total value generated by this relationship, with the client walking with the lion’s share. Depending on the rate of fees, the advisor’s lifetime share for the example 45-year-old works out to around 24% to 32% of the total value generated, as demonstrated below.

Example Projections

This model allows inputs for many characteristics: Age, net worth, income, retirement age, inflation, advisor fees, expected returns, and more. It offers a way to quantify potential value of the client-planner relationship amidst ambiguity. For example, plugging the following client profiles into the model yields the following outputs:

The model can also estimate trends of the value of advisors depending on different factors, while holding others constant. For example, starting net worth and starting age can have large impacts on the value of an advisor for a given client, all other things held constant, as demonstrated below.

Net Worth

Similarly, we can compare how starting capital impacts the overall outcome of employing an advisor. Thanks to the better fee negotiation capabilities and the effects of compounding, those with more capital on the line stand to gain more.

Age

The effects of compounding also mean that initiating a client-planner relationship at a younger age yields more benefits over time, regardless of your starting net worth or income.

Interviewing Advisors to Get the Best Value

In practice, outcomes of the client-advisor relationship will depend on the competence and fit of the individual advisor, in addition to the contextual circumstances. This means you should interview several advisors to get the best sense of what each can offer to your unique circumstances. It’s important to find someone you feel you can communicate with comfortably and effectively.

A good advisor should ask about your personal circumstances and goals to help you understand what type of value they can offer you. It may feel daunting to share personal financial information and aspirations with someone you just met, but it’s important to be able to be open and honest with your advisor to get the best results.

Some examples of questions you may want to ask advisor-interviewees include:

- What are your qualifications and experience in financial planning?

- Are you a fiduciary, and what does that commitment mean in practice?

- Who are your typical clients?

- How do you get compensated?

- Can you provide a sample financial plan?

- How often do you communicate with clients

- How do you handle market downturns?

- What investment philosophy do you follow?

- Can you explain your approach to risk management?

- How do you personalize your advice to individual client needs?

- What is your process for ongoing financial education and staying updated with financial laws and trends?

It may be prudent to ask about the advisor’s experience in specific areas that are important to you, as advisors may specialize in certain areas of personal finance. Remember that selecting a financial advisor is not just about finding someone with expertise, but also about forging a partnership that aligns with your financial vision and personal comfort. The right advisor will not only navigate you through the complexities of financial planning but will also empower you to make informed decisions, ensuring that your financial journey is both secure and tailored to your life’s goals. Your due diligence in this selection process is an investment in itself, promising dividends in peace of mind and financial well-being.

SmartAsset can match you with vetted fiduciary financial advisors with this free tool.

And if you’re a financial advisor, learn what SmartAsset has to offer to help you grow your practice.

References

¹ Dalbar. Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) report, 2024.

² TipRanks. Analyst returns were compared to the S&P 500 returns over a 1-year period. Data was collected through July and August 2024.

³ Vault Wealth Management. How Much Money Can a Tax Professional Save You on Average? 2017.

⁴ U.S. Census Bureau. Improvements to Measuring Net Worth of Households: 2013.

⁵ Coin News Media Group. U.S. Inflation Calculator. Historical Inflation Rates: 1914-2024. Annual average taken for 2000 through 2023.

⁶ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED). Personal Saving Rate, Percent, Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate. January 2000 through August 2024.

⁷ Center for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. Life Expectancy.

⁸ DQYDJ. S&P 500 Return Calculator, with Dividend Reinvestment. January 2000 through August 2024.

⁹ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED). Moody’s Seasoned Aaa Corporate Bond Yield, Percent, Monthly, Not Seasonally Adjusted. January 2000 through September 2024.

This is a hypothetical example and is not representative of any specific security. Actual results will vary.

This is not an offer to buy or sell any security or interest. All investing involves risk, including loss of principal. Working with an adviser may come with potential downsides such as payment of fees (which will reduce returns). Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. There are no guarantees that working with an adviser will yield positive returns. The existence of a fiduciary duty does not prevent the rise of potential conflicts of interest.

SmartAsset.com is not intended to provide legal advice, tax advice, accounting advice or financial advice (Other than referring users to third party advisers registered or chartered as fiduciaries (“Adviser(s)”) with a regulatory body in the United States). The article and opinions in this publication are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. We suggest that you consult your accountant, tax, or legal advisor with regard to your individual situation.

It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Exposure to an asset class represented by an index may be available through investable instruments based on that index. Past performance of an index is not an indication or guarantee of future results. Indexes do not pay transaction charges or management fees.

The above summary/prices/quote/statistics has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable, but we cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This scenario is for illustrative purposes only and does not represent an actual client. Results may vary.

SmartAsset Advisors, LLC (“SmartAsset”), a wholly owned subsidiary of Financial Insight Technology, is registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission as an investment adviser. SmartAsset’s services are limited to referring users to third party advisers registered or chartered as fiduciaries (“Adviser(s)”) with a regulatory body in the United States that have elected to participate in our matching platform based on information gathered from users through our online questionnaire. SmartAsset receives compensation from Advisers for our services. SmartAsset does not review the ongoing performance of any Adviser, participate in the management of any user’s account by an Adviser or provide advice regarding specific investments.

We do not manage client funds or hold custody of assets, we help users connect with relevant financial advisors.